The Paul, Weiss Antitrust Practice advises clients on a full range of global antitrust matters, including antitrust regulatory clearance, government investigations, private litigation, and counseling and compliance. The firm represents clients before antitrust and competition authorities in the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom and other jurisdictions around the world.

The European Commission Proposes a New Approach to Enforcement of Exclusionary Abuse of Dominance

People

August 6, 2024 Download PDF

- The European Commission has just published an updated draft of its guidelines on exclusionary abuse of dominance under Article 102 TFEU.

- The draft puts forward a new structure for enforcement against exclusionary abuse of dominance: it introduces a new

two-stage test; it argues for the Commission to have the broad ability to find an abuse in novel situations; and it sets out a presumption-based approach to enforcement in this area. - In this memorandum, we look at the new approach taken in the draft guidelines in light of existing European court precedent on exclusionary abuse of dominance, and also offer some points of comparison to the similar but different offence of monopolisation under United States federal law.

On 1 August 2024, the European Commission published an updated draft of its guidance on exclusionary abuses of dominance under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The current guidelines have framed the Commission’s approach to this area for more than 15 years during a time in which these cases came under intense scrutiny, especially in the technology and pharmaceutical industries.

The draft guidelines, which “aim at reflecting the Commission’s interpretation of the EU courts’ case law,” seek to create a revised “enforcement blueprint” that will enable the Commission to cut through the evidentiary and procedural burdens of these cases to enable quicker and more effective enforcement. While this goal was shared by the Digital Markets Act—which regulates the behaviour of certain gatekeepers in the digital industry—the draft seeks to provide an improved framework for enforcement of Article 102 TFEU against all dominant firms, and to influence future judgments of the European Courts.

U.S. Comparison. The guidelines’ ability to look back over the past 15 years on a significant body of judicial precedent is notable when contrasted with the development of monopolisation case law in the United States: there simply have not been many opportunities for courts to opine on this area of the law in recent decades. This, of course, has changed markedly, beginning with the prior administration. According to one recent statistic, the DOJ alone has more monopolisation cases currently pending in the courts than in the previous 20 years combined, with reports of more potential actions in the pipeline. And one must add to this several pending actions brought by the FTC.

Key features of the EC abuse of dominance guidance

Dominant position

Like its predecessor, the draft first describes how the Commission will assess whether a given undertaking may have a dominant position, which starts with the firm’s market position and that of its competitors, before considering the broader features of the relevant market (e.g., barriers to expansion and entry and countervailing buyer power). According to the draft guidelines, a “very large market share,” in particular 50 per cent and above, is indicative of a dominant position, though dominance has been established based on lower market shares, as the guidelines make clear.

U.S. Comparison. The U.S. offence of monopolisation requires much more than a dominant position. It requires the existence of “monopoly power.” Monopoly power is described in the case law as “the power to control prices or exclude competition.” This can be shown by direct evidence of exclusion, restricted output and high margins; but more often it is inferred from very high market share—generally in excess of 70 per cent—coupled with high barriers to entry. The difference between the 50 percent share associated with a dominant position and the 70 per cent share associated with monopoly power is perhaps the most significant difference between EU and U.S. antitrust law generally applicable to single-firm conduct. (Another notable difference, though directed at a specific type of firm, is of course the Digital Markets Act.)

Exclusionary abuse of dominance

Most importantly, the draft Commission guidelines then seeks to codify a two-part test for exclusionary abuse of dominance under Article 102: (1) has the conduct departed from the principle of competition on the merits; and (2) is the conduct capable of excluding competitors? While these considerations do feature in European Court precedent, the draft is novel in setting up this test clearly and in two parts and in introducing several legal presumptions to govern the Commission’s enforcement efforts.

Has the conduct departed from the principle of competition on the merits?

According to the draft guidelines, the Commission can deem this to be the case for conduct that satisfies a legal test established by the European Courts. Likewise, conduct that holds no economic interest for the dominant firm except restricting competition is “deemed as falling outside the scope of competition on the merits.”

For other types of conduct, the draft codifies a list of criteria that the European Courts have previously used in establishing competition off the merits:

- Whether the undertaking prevents consumers from exercising their choice based on the merits of the products.

- Whether the undertaking provides misleading information to administrative or judicial authorities, or misuses regulatory procedures, to prevent or make it more difficult for competitors to enter the market. (These issues have been the subject of recent national enforcement in the pharmaceutical sector by the Danish (Falck) and French (Novartis) Competition Authorities following the European Court’s 2012 AstraZeneca)

- Whether the undertaking violates rules in other areas of law (e.g., data privacy law) and thereby affects a relevant parameter of competition (see the European Court’s recent judgment in Meta, which confirmed that breaches of data protection laws by a dominant undertaking can result in a breach of Article 102).

- Whether the undertaking’s conduct consists of, or enables, biased or discriminatory treatment that favours itself over its competitors.

- Whether the undertaking changes its prior behaviour in an abnormal or unreasonable way (e.g., the unjustified termination of an existing business relationship).

- Whether a hypothetical competitor as efficient as the dominant undertaking would be unable to adopt the same conduct, notably because the conduct relies on the use of resources or means inherent to the holding of the dominant position.

Is the conduct capable of excluding competitors?

According to the draft guidelines, the Commission need only prove that conduct be “capable” of excluding rivals; it need not demonstrate actual effects. It is also enough that the conduct reduce competitors’ ability or incentive to exercise a competitive constraint; exclusion is not necessary and there is no de minimis threshold. This approach, as in many other areas of ECJ jurisprudence, brings Article 102 enforcement in line with Article 101.

The draft then establishes a sliding scale of presumptions through three categories of conduct:

- A “hard” presumption for conduct that has no economic interest for the dominant firm other than restricting competition. The guidelines provide three examples of “naked restrictions” of this nature: payments to customers that are conditional on postponing/cancelling the launch of products based on supplies by the dominant firm’s rivals; the dominant firm agreeing with its distributors to swap a competing product with its own under the threat of withdrawing discounts; and the dominant firm actively dismantling infrastructure used by a competitor (as was the case in Lithuanian Railways). They note that a firm could in theory prove that conduct in this category was not capable of excluding competitors or that it was based on an objective justification but that these would be exceptional outcomes.

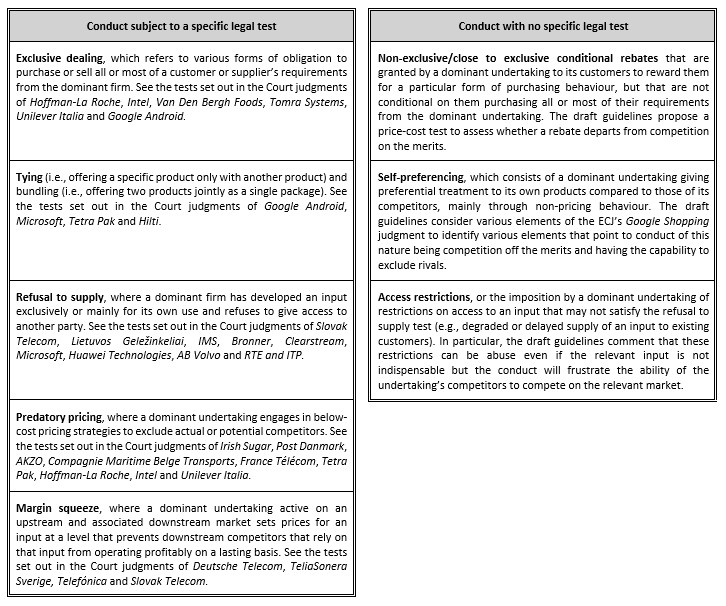

- A “soft” presumption for conduct that falls short of naked restrictions but is nevertheless likely to produce exclusionary effects. The draft guidelines make explicit reference to five types of conduct where a “legal test” has been established by the European Courts (exclusive dealing, refusal to supply, predatory pricing, margin squeeze and certain forms of tying). Where the legal test is met, the guidelines claim that the Commission need not separately establish that the conduct is capable of excluding competitors (nor that it reflects competition off the merits). Where a company seeks to rebut that presumption, the guidelines note that the Commission will need to either (1) show that rebuttal is insufficient to call the presumption into question (e.g., due to the insufficient probative value of the evidence or because the arguments refer to theoretical assumptions rather than the competitive reality of the market), or (2) carry out an effects-based analysis that “give[s] due weight to the probative value of a presumption, reflecting the fact that the conduct at stake has a high potential to produce exclusionary effects.”

- A residual category where the Commission does need to demonstrate that the conduct is capable of excluding competitors; the Commission will need to assess these cases holistically based on conventional factors such as the company’s market position, barriers to entry, the ability of the conduct to tip the market or to further entrench the company’s position, and the extent of the conduct at issue.

U.S. Comparison. In addition to monopoly power, U.S. monopolisation law also requires the existence of anticompetitive conduct. Rather than explicitly defining a two-part test to identify conduct that is outside the bounds of competition on the merits and capable of excluding competitors, an often-cited U.S. Supreme Court opinion refers to “the willful acquisition or maintenance of [monopoly] power as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident.” U.S. law would appear to subsume the “capability” prong of the two-part EC test for abuse of dominance within the definition of monopoly power, i.e., “the power to exclude.” (Some U.S. judicial opinions actually use language very similar to the Commission’s, referring to “conduct, other than competition on the merits . . . that reasonably appear[s] capable of making a significant contribution to creating or maintaining monopoly power.”) However described in judicial opinions, the shorthand term “exclusionary conduct” suffices to describe a second factor for a U.S. monopolisation claim.

Some of the behaviours enumerated by the Commission as conduct indicative of competition off the merits have rough analogues in the U.S.. But others have in fact been rejected as a basis for antitrust liability. For example, in the very limited circumstances in which a unilateral refusal to deal could be grounds for an antitrust offence in the US, courts require, among other things, proof that the defendant terminated a profitable course of dealing—similar to one of the Commission’s criteria for competition not on the merits. Yet, as one counterexample, in 2016 an appeals court held that false advertising can serve as the basis for an antitrust suit only in the extreme case where “a competitor’s false advertisements had the potential to eliminate, or did in fact eliminate, competition.” This would appear to contrast with one of the criteria that the Commission uses to establish “competition off the merits.”

Notwithstanding the similarities and differences in the types of conduct that could support single-firm conduct claims under EU and U.S. antitrust law, one overarching difference is that in the United States, courts generally require a plaintiff to demonstrate that the conduct in question had anticompetitive effects – or at least that it is likely to have anticompetitive effects. Conduct that is merely “capable of excluding competitors” will not suffice.

Specific types of conduct

The draft guidelines set out a more detailed summary of the various categories of conduct that have been the object of European Court judgments and in doing so distinguishes between conduct that has been subject to specific legal tests and that without a specific legal test; as noted above, the guidelines claim that this is relevant for determining whether the Commission can deem that a given course of conduct is inconsistent with the principle of competition on the merits.

|

U.S. Comparison. Just as in the EU, U.S. courts over the years have defined several types of exclusionary schemes that violate the law, some more aligned with their foreign counterparts than others. While an in-depth comparison of the elements of each of these is beyond the scope of this memorandum, we note that both jurisdictions recognize some form of exclusive dealing, predatory pricing, tying and—to a very limited extent, at least in the U.S.—refusal to deal as conduct that could give rise to a single-firm antitrust offence. With any similarities, however, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that EU law necessarily captures much more single-firm conduct under its antitrust law that the U.S. does under its laws for the simple reason that the market share threshold for single-firm liability is much lower in the EU.

Concluding remarks

The Commission will no doubt argue that the guidelines merely codify the jurisprudence of the European Court in this area. However, they provide a much more radical restructuring of the Commission’s enforcement of Article 102 than many had anticipated: they introduce a new two-stage test (conduct departing from competition on the merits; and capability of exclusionary effect); they argue for the Commission to have the broad ability to find an abuse where these criteria are met without regard to an exclusive list of abuses (making it considerably easier to do so); and they introduce a new set of presumptions that seek to expedite Commission enforcement.

The Commission will be hoping that the European Courts pay as much attention to these new guidelines as do dominant firms. Its current set of guidelines emphasise the need for an effects-based assessment in this area, which led to a period featuring a slow pace of enforcement, especially in several leading cases featuring complex and dynamic markets. The presumption-based approach set out in the revised draft therefore strikes at the heart of an ongoing debate around antitrust enforcement under Article 102. The Commission will hope that this document sets the stage for a new era of quicker enforcement and that the European Courts support its efforts when the inevitable appeals arrive in Luxembourg. In the shorter term we anticipate a lively and important debate around this proposal in the coming months.

* * *