The Paul, Weiss Antitrust Practice advises clients on a full range of global antitrust matters, including antitrust regulatory clearance, government investigations, private litigation, and counseling and compliance. The firm represents clients before antitrust and competition authorities in the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom and other jurisdictions around the world.

European Commission Competition Report Spotlights Potential Areas of Focus for Next Commissioner

July 3, 2024 Download PDF

Key Takeaways

Last week, the European Commission (EC) Directorate-General for Competition published a staff report on ‘Protecting competition in a changing world: Evidence on the evolution of competition in the EU during the past 25 years’. We have read the report and believe that one can distill from it several principles that may guide competition policy in the next Commission:

- strong and focused competition law enforcement will be a priority for the EC in the coming years, particularly in the sectors of interest identified within the report – namely telco, gas, software, airlines, rail, pharma, and consumer goods (particularly those with high spending from lower socioeconomic demographics);

- to improve its competitiveness, Europe needs more innovation and investment – however, this will not happen without effective competition which, in turn, requires continued strong competition law enforcement;

- further consolidation is not required for more innovation and higher investment in strategic sectors – the telecoms sector is the focus of the report (given previous attempts at 4:3 mergers in the sector), but the conclusion applies across the board; and

- ‘competition at home’ is key for European companies to compete globally (i.e., there is a need to push back on calls for European champions).

The report appears to be the latest salvo in DG Competition’s attempts to stave off dilution of its competition powers. The last significant part of this effort was passage of the Foreign Subsidies Regulation, which was borne in part out of a desire to avoid polluting competition policy with the political fallout which accompanied the Commission’s block of the Alstom-Siemens merger (which was characterized as a merger of French and German “champions” to meet competition alleged to arise from government-subsidized Chinese manufacturers).

The report signals that the Commission’s focus will be on the protection of competition and innovation competition (i.e., dynamic competition), particularly in sectors with existing high levels of concentration and clear signs of market power.

The report’s conclusions in relation to lower income households and consumer-facing sectors suggest that these will be critical areas of focus for antitrust and merger enforcement going forward, with a potential goal of increasing the purchasing power of consumers to both reverse trends at the macro-economic level and improve competition. We expect that the EC may focus on these sectors in its enforcement strategy to send a message to other market participants.

Specifically for private equity deals, the report asserts that common ownership has been a structural driver for purported negative changes to competition, indicating a belief that common ownership (even at small minority levels) can influence competitive dynamics.

We do not expect any major changes in substance to the EC’s approach in merger review. For antitrust enforcement, however, the report suggests a willingness to consider novel theories of harm whilst being open to discussion on effective remedies to protect innovation competition.

Background and summary of report

The Commission’s report assesses the conditions of competition in the EU over the last 25 years and the main drivers of change, presenting new findings based on extensive economic research on the impacts on overall economic growth. The Commission draws on contributions from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a consortium of researchers led by economics consultancy Lear, and by the Chief Economist’s team within DG Competition itself. It provides an update on the current factors affecting competition in the EU, the key drivers for this, and the impact of competition on economic outcomes.

The report, which was presented and discussed at a conference hosted by the EC on 27 June 2024, comes at a crucial political juncture for Europe. In particular, current European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen will soon need confirmation from the European Parliament to renew her mandate. The vote is likely to be close. In exchange for supporting President von der Leyen, certain members of the European Parliament will likely seek concessions and there likely will be calls for a more interventionist industrial policy and more ‘benign’ enforcement of competition policy. These calls will likely be echoed in a report on European competitiveness expected to be issued by Mario Draghi (the former Italian Prime Minister and European Central Bank President) at the end of July. All of this will inform the selection of the next Competition Commissioner, the hearings in European Parliament of Commissioner-designates, and the EC’s key policy priorities for the next five years. Indeed, there has already been mounting pressure to relax competition law enforcement in the next commissioner’s mandate -- notably in the area of mergers, but also in relation to state aid. The report, however, may be one means by which current Commissioner Margrethe Vestager will try to resist this pressure.

Key findings of the report

Overall, the report finds weaker intensity of competition in the EU than in the past, with more pronounced market power and profit for firms at the top. However, the Commission caveats this with the finding that such weakened competition is still less pronounced than in other economies such as the United States.

Changes to competitive intensity have been driven by both structural and institutional changes to how firms create value and compete in today’s economy. The EC addresses how technological innovation, digitisation of business, public policies, and transformation in global supply chains (exemplified by China’s re-integration into global trade) have changed the dynamics of trade and competition.

The second part of the report confirms and supplements prior findings that competition can have effects on prices and purchasing power of consumers, competitiveness of EU firms and overall economic growth. This is correlated to productivity, the most important factor for overall competitiveness and economic growth, with the research estimating that increased markups over the last 25 years might have reduced EU GDP by five to seven percent.

These key findings are discussed in more depth below.

Evolution of competition

The report asserts that on average and in a wide range of sectors in the last 25 years:

- concentration at industry and market level has increased (by approximately five percent on average);

- mark-ups and profits at the top of distribution have increased, particularly for ‘global superstar’ firms i.e., the most profitable large global firms;

- the gap between industry leaders and followers has increased; and

- business dynamism (measured by market share volatility between leading firms or entry/exit rates) has declined, particularly in consumer goods sectors.

Drivers of evolution of indicators of competition

As changes to competition have been across many sectors of the economy, the EC suggests that the changes have occurred due to both structural and institutional drivers.

Structural drivers. Structural drivers include rising investments in proprietary IT solutions and data, other intangible investments, globalisation, and changes to business conduct (i.e., M&A, oligopolistic pricing and behaviour, exclusionary strategies and common ownership by shareholders). In particular, the EC observes a link between access to intangible assets such as software and indicators of weakened competition.

‘Winner takes most’ dynamics mean that large first-mover firms have been able to reap most of the benefits. The EC considers that this winner-takes-most framework initially enhances productivity growth. However in a second stage, it inhibits the process. That is, trends show that once a firm has established dominance through initial structural efficiencies, it then becomes easier to engage in exclusionary conduct, leading to high barriers for new entrants. During the EC’s conference on the study on 27 June, Professor Nancy Rose at MIT Economics described this two-phase exclusionary behaviour as ‘getting to the top and then pulling up the ladder behind you’.

Whilst the rise in M&A and potential underenforcement are flagged by the EC, it doesn’t attribute these to reduced competition.

Institutional drivers. Institutionally, the report observes regulatory barriers to entry and expansion contributing to these ‘winner takes most’ dynamics. In this respect, more vigorous competition enforcement in the EU as an institutional driver is attributed to less adverse effects than in the United States.

Recent shocks to the EU economy are mentioned in the report, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia-Ukraine war, and rising inflation in the context of whether the EU competitive process is resilient and flexible enough to adapt to similar shocks in the future. However, no concrete conclusions are made.

Specific sectors of focus

Across 127 sectors, the report presents a scorecard of competition levels according to each sector’s performance against the indicators of competition identified (i.e., concentration, mark-ups, profits, and measures of business dynamism). Having ranked each sector’s degree of competition (according to the indicators), the report concludes that regulatory intervention has been most frequent in sectors with high competition risks based on the sectoral scorecard. Highest ranking on the scorecard include gas, telecoms, pharmaceuticals, rail transport, beverages, cement, and aerospace.

According to the report, technological change and globalisation have had benign competitive effects on unconcentrated sectors or sectors where technological and business process innovations improve competition (for example, retail, car manufacturing and the manufacturing of semiconductors). At the other end of the spectrum, technological change and globalisation have, according to the report, led to a widening of the gap between leading firms and followers. Limited churn/dynamism at the top have been more detrimental to consumers in sectors such as consumer goods for household and personal care products, breakfast cereals, carbonated soft drinks, tobacco or beer, or in business-to-business sectors such as aircraft manufacturing, cement, and pesticides and seeds, according to the report. The report posits that sectors such as software and pharmaceuticals exhibit both benign and adverse consequences of such structural drivers, with technical progress simultaneously benefiting consumers but increasing barriers to entry.

Several sector-based nuances bear mention:

- core upstream markets: technological change and globalisation have potentially harmful effects on competition where they influence core inputs for doing business – like in telcoms, gas, and software;

- increased consolidation: particularly negative impacts on competition were seen in sectors with increasing consolidation, particularly in telcoms and airlines;

- higher levels of lower socioeconomic spending: with concentration particularly high in product markets that make up a high share of poorer households’ expenditure and which have contributed to the recent surge in inflation i.e., food and energy;

- markets with ‘winner takes most’ dynamics: with rising profits in IT (in particular, the ‘GAFAMs’), pharmaceuticals and consumer goods linked to high barriers to entry enjoyed by dominant firms (with harmful mergers and strategic exclusionary conduct in these sectors);

- highly concentrated markets: increased prices relative to concentration are observed in sectors (relative to input costs) such as mobile telecom services, air transport services, beer, mortgage rates, and cement.

Whilst the EC has observed variances by sector, it has taken the view that intensity of competition in the EU is now weaker overall.

Impacts on macro-economic trends

The Commission also considers effects on worrying macro-economic trends such as reductions in productivity growth, wage inequality, lower investments, and overall lower economic growth.

More effective competition resulting in lower markups, could have macroeconomic benefits in the reduction in price levels, increased household consumption and private investment, a strengthening of productivity and overall economic growth, according to the report.

The report estimates the weakening of competition since 2000 may have led to a five to seven percent drop in GDP, a four to five percent increase in prices and a one to three percent drop in productivity, with a potential worsened outcome by 25 percent were it not for EC interventions in the last 10 years. The report also estimates that implementing measures to limit market power of dominant firms may increase GDP by two to four percent.

Why competition matters for economic outcomes

The report posits links among competition, the competitiveness of companies and macro-economic trends, such that weakened competition harms productivity and long-term economic outcomes. The report also states that firms experiencing strong competition at a domestic level perform better globally, based on studies of successful export sectors. That is, domestic competition incentivises improvements to product quality, efficiency, and innovation.

Key observations of the report’s authors

We note the following key conclusions and messages in the Commission’s report:

- Comparison to United States. The report claims that there are problems in competition in the EU evidenced by increased concentration, mark-ups, and profits. The authors also state that these indicators are less pronounced in the EU than in the United States and that the EU may have been worse if not for focused competition law enforcement. The authors caveat this conclusion with an assertion that the United States differs in certain respects from the EU in ways that purportedly lead to worsened competition effects – including that, according to the report, the United States has a greater presence of ‘superstar’ firms.

- Conclusions as to concentration and dynamism. The report states that increased concentration is observed to lead to oligopolistic markets and increased risk of unilateral and coordinated effects. However, the Commission also observes that high concentration can still be competitive for dynamic oligopolies.

- Sequential ‘winner takes all’ structural dynamics. The EC recognises that even where higher concentration may have benign drivers in initial phases (i.e., digitisation, globalisation, and innovation) which benefit consumers, this fact will be irrelevant if the dominant firm then exploits its power to reduce competition in an already concentrated market.

The report discusses the importance of protecting innovation in the initial phases whilst also protecting against exploitative conduct once the ‘benign effects’ phase has passed and the firm has obtained dominance. This suggests a link between the report and the EC’s approach to enforcement of Article 102 of the TFEU, where the EC will notably focus on how to ‘facilitate’ the determination of an abuse without compromising the legal standard. This may facilitate the EC’s theory of harm for exploitative conduct in Article 102, which is relative to the market dynamics and the advantages that the dominant firm then enjoys.

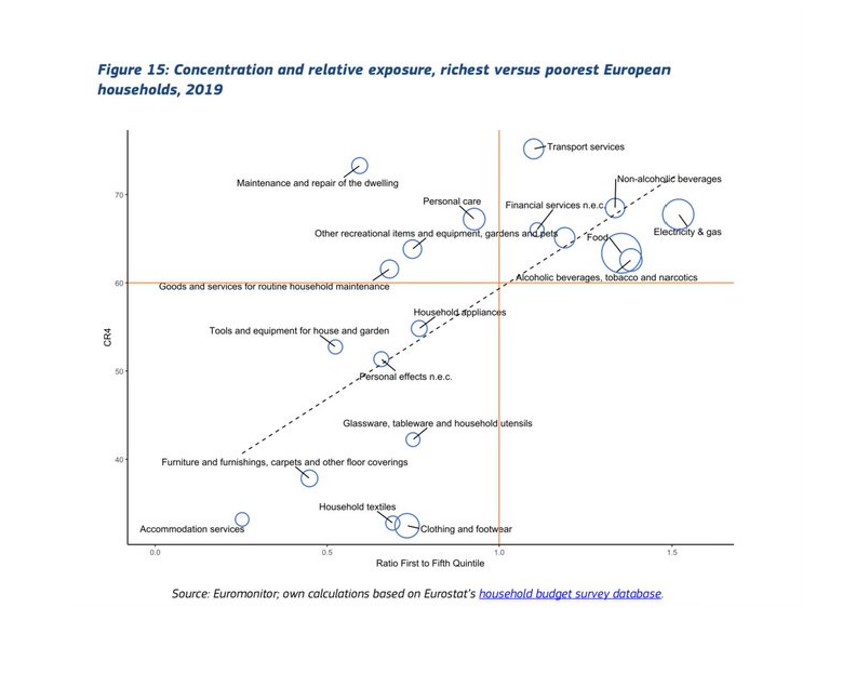

- Reduced competition impacts lower income households in particular. The report posits that lower income households are more heavily exposed to more concentrated markets:

|

- Focus on ‘superstars’. The EC is focused on ‘super stars’ which include both digital/pharma and ‘consumer facing’ sectors, suggesting a focus on improving purchasing power of consumers.

- Under-enforcement. Interestingly, findings of weaker competition are not attributed to the Commission’s own intervention approach or whether there has been under-enforcement. Conversely, the report conducts a detailed analysis of the relationship between levels of competition and level of enforcement, concluding that intervention and enforcement have effectively enhanced competition/limit reductions to factors contributing to competition.

Similar findings in other jurisdictions

Similar findings, particularly in relation to increased concentration and its links to mark ups and profits, have been made in the United States, both by the Council of Economic Advisors in 2016 in their report ‘Benefits of competition and indicators of market power’ and the Chairperson of the Federal Trade Commission in 2018 in its contribution to the Quarterly Journal of Economics ‘The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications’. The 2016 report has since been cited by the Federal Trade Commission and the White House, including in the release of more stringent merger guidelines in July 2023.

The Competition and Markets Authority in the UK drew similar conclusions in its 2022 ‘state of UK competition’ report, finding that the largest and most profitable firms are able to sustain their market position for longer than prior to the global financial crisis. This report notably conducted a more detailed analysis into common ownership and its effect on market concentration, and is similarly focused on end-consumer outcomes.

* * *