Led by the nation’s foremost legal specialist on the intersection of artificial intelligence and the law, as well as world-class litigators and IP-focused lawyers fluent in the latest AI and machine-learning tools and their applications, our cross-departmental AI team is uniquely positioned to help clients mitigate potential legal and business risks in their use of AI-powered technologies, while safely taking advantage of the business opportunities presented by these powerful new tools.

The EU AI Act Is Almost Here: Applicability, Timeline, and Next Steps

July 16, 2024 Download PDF

On July 12, 2024 the European Union’s landmark AI regulation (the “Act”) was published in the Official Journal of the EU. This publication will mark the start of the twenty-day countdown until the Act comes into effect on August 2. Publication of the Act in the Official Journal of the EU represents the culmination of a years-long, and sometimes tumultuous, process.

In this alert, we provide our key takeaways and a high-level roadmap for charting compliance with the Act, noting important steps and considerations that businesses may wish to take into account. We then review the core provisions of the Act, including its applicability to various entities in the AI value chain and the key obligations for these entities, as well as the staggered timeline on which the Act takes effect.

Takeaways

The Act is broad in scope and it will take time for regulators and industry bodies to interpret and enforce its provisions. In particular, guidance required under the legislation is still awaited. However, there are a number of key takeaways for all businesses to consider in the early days of the Act as they build out their compliance function:

- Territorial scope: The broad geographical scope of the Act will implicate a significant number of AI Systems and GPAI models. Not only will those doing business in the EU need to comply, but businesses will need to consider early whether outputs of their AI System bring them in-scope because they are used within the EU. While eventual European Commission guidance may clarify this concept over time, it will be important for non-EU businesses to consider the nature and use of their outputs and what guardrails should be implemented to keep them out of scope, if desired.

- Prioritized approach: A top priority should be determining whether a business’s current or proposed AI activities could fall within a “prohibited practice” or “high-risk” AI System category, or whether any of a developer’s GPAI models will pose “systemic risk,” especially in light of the high fines for non-compliance, and the relatively short timeline before the prohibitions and GPAI model-related obligations come into effect.

- Governance: Businesses should also prioritize implementing proper governance and risk management procedures and templates, which are well designed to promote compliance with applicable requirements (including the need to conduct a fundamental rights impact assessment prior to use of high-risk AI Systems).

- Transparency: Even if an applicable AI System is not prohibited or categorized as high-risk, there are a number of transparency obligations that could apply. For example, providers of general-purpose AI models intended to interact directly with individuals (including customers and employees) must inform those individuals that they are interacting with an AI System (unless otherwise obvious to the person) and there are additional transparency obligations for emotion recognition systems, biometric categorization systems and deepfakes, amongst others, subject to certain exceptions.

- General-purpose AI (“GPAI”). Separate obligations will apply to GPAI models, irrespective of risk categorization, and additional obligations also apply to general-purpose AI models designated to have “systemic risk”—a category targeted at the largest state-of-the-art AI models. All GPAI models will be subject to specific transparency obligations (including information about training data used and use of copyrighted works). The additional obligations for those GPAI models with “systemic risk” include adversarial testing, assessment and mitigation of systemic risk, reporting serious incidents, ensuring adequate cybersecurity, and energy consumption reporting. Businesses that develop or invest in GPAI models should consider how the Act might affect their products.

- Building Out the AI Office. The Act provides for the establishment of an AI Office, which will, among other functions, issue guidance to inform interpretation and implementation of the Act. The AI Office will also provide coordination support for regulatory investigations. The EU announced the Office’s establishment on May 29, 2024, with recent reports suggesting it is still filling vacancies – we will be watching as it takes shape.

- Guidance, Codes of Practice and Standards. The AI Office, along with specific standards-setting bodies (such as the European Committee for Standardization (“CEN”), European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization (“CENELEC”), and the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (“ETSI”)), are tasked with producing guidance and codes of practice to facilitate compliance with key obligations. Given the numerous stakeholders and relatively tight turnaround to establish certain guidance, we anticipate that the AI Office may rely heavily on the input of interested parties, which will start in earnest in short order. Covered businesses should consider whether to engage with the AI Office and other bodies to help shape the relevant guidance, codes of practice and standards – particularly those industries that will likely fall into the high-risk categorization or where a helpful exemption may apply. This input is likely welcomed, as the AI Office has already put out a call for a wide range of stakeholders to participate.

- The EU Revised Product Liability Directive and AI Liability Directive. There are two additional EU directives that will potentially also have a substantial impact on the AI legal and regulatory landscape. The Revised Product Liability Directive extends the existing EU product liability regime to include software and AI, including a rebuttable presumption that the product-at-issue was defective. The new directive still awaits adoption by the Council of the EU and once it is in force will require implementation by national legislation in member states within 2 years. EU legislators were also working on the AI Liability Directive, which would ease the burden of proof for victims seeking to establish damage caused by an AI System by creating a rebuttable “presumption of causality” against the AI System’s provider or user. It would also introduce extensive disclosure obligations (which are not standard in civil litigation in most member states). However, the timeline for adoption of this directive is unclear and there is little indication for appetite to advance this directive in the short term.

Though after many years of speculation, negotiation and disagreement the Act is almost effective, there is time left before providers and deployers must comply with its core provisions (although the prohibitions will take effect in 6 months). Nevertheless, covered providers and deployers should take advantage of this transition period to advance their preparations to ensure that a robust compliance program is in place once the various provisions take effect.

Below, we provide an overview of the EU AI Act’s scope and key obligations. These obligations are not exhaustive but rather illustrate the varying compliance requirements imposed on entities at different points of the AI value chain, based on the specific use of the AI and the type of technology at-issue.

The EU AI Act’s Applicability

What is an “AI System”?

The Act covers any “AI System,” which is defined as “a machine-based system designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy, that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments.” This definition bears a close resemblance to the language adopted by the OECD that gained significant airtime with policymakers and regulators in recent years.

As noted, there are additional rules for GPAI models, i.e., AI models trained with larger amounts of data and which display significant generality and capability to perform a wide range of tasks.

These definitions are likely to receive further clarification as the European Commission and standards-setting bodies bring out guidance on their interpretation, but they currently capture a significant number of systems and models.

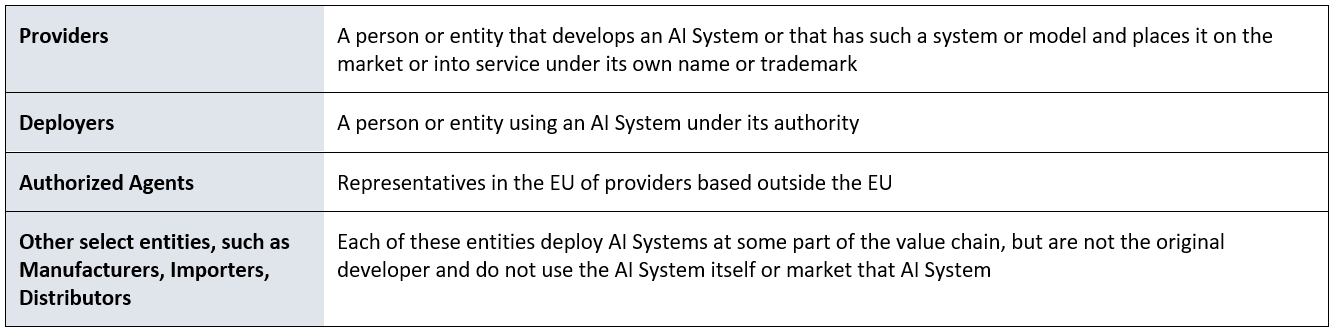

Who is covered?

The Act is intended to capture the activities of a broad range of entities and businesses, applying to:

Each type of entity is subject to a different set of obligations, with the majority of obligations applying to providers.

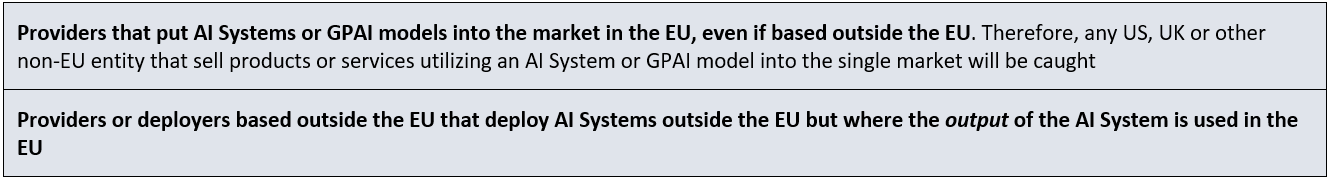

What is the territorial scope?

The Act has a broad extraterritorial scope, covering not only businesses that are based or incorporated within the EU but also:

This broad reach has led to an expectation that the Act, as with the General Data Protection Regulation before it, will generate the “Brussels effect,” whereby the legislation strongly influences the development of similar legal regimes worldwide. We are already witnessing this trend, with jurisdictions such as Brazil, Chile, and Peru taking inspiration from the Act.

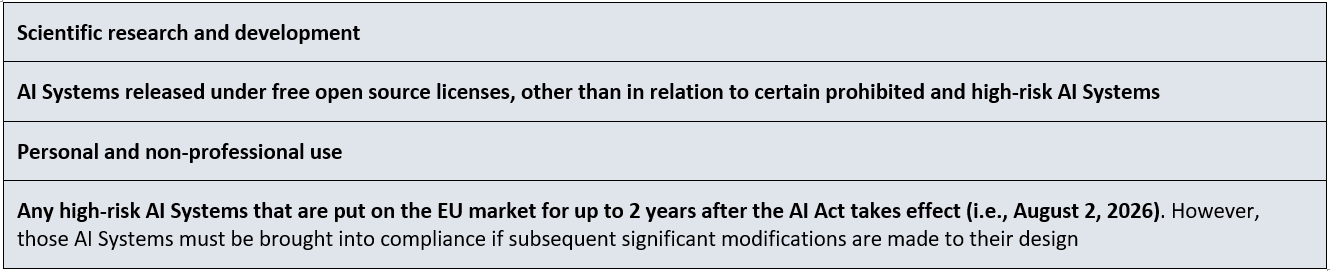

Are there any exemptions?

The Act includes certain express exemptions from its coverage, including but not limited to:

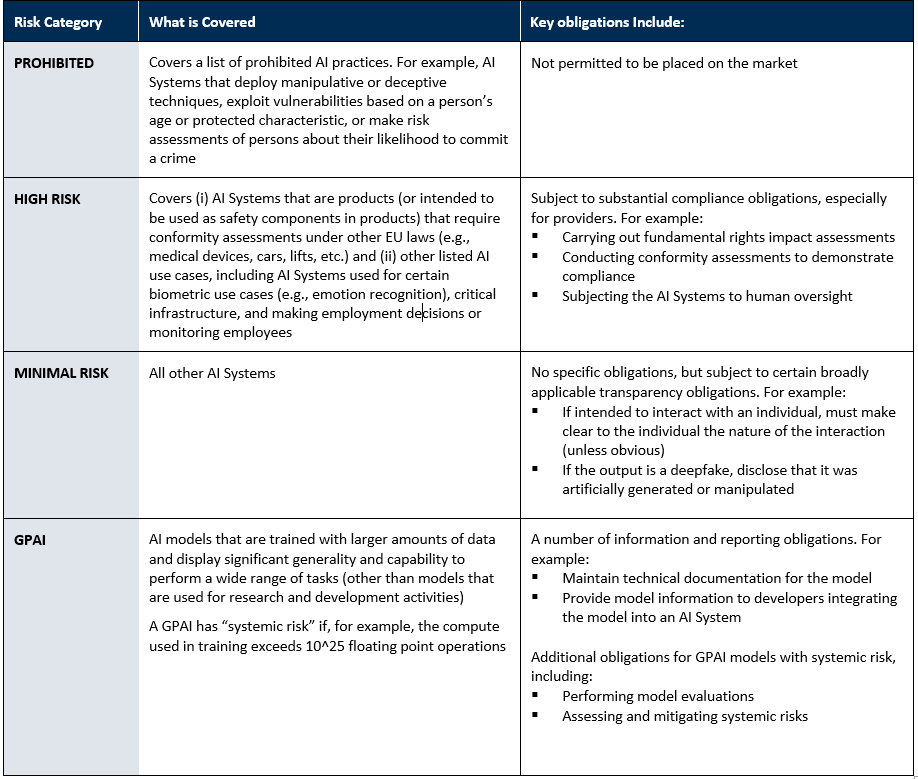

The EU AI Act’s Obligations

The obligations under the Act generally apply based on the risk associated with the AI System or GPAI model’s use case. There are four categories of risk accounted for in the Act, each of which requires its own suite of compliance steps.

Penalties

EU member states must provide rules on penalties and enforcement measures (including non-monetary enforcement measures), but the Act sets out the following administrative fines: (i) partaking in prohibited practices – the greater of €35 million and 7% of global annual group turnover; (ii) other breaches (including to providers of GPAI models) – the greater of €15 million and 3% of global annual group turnover; and (iii) supply of incorrect or misleading information to notifying bodies – the greater of €7 million and 1% of global annual group turnover. Enforcement is required to be effective, proportionate and dissuasive.

Timeline for Implementation

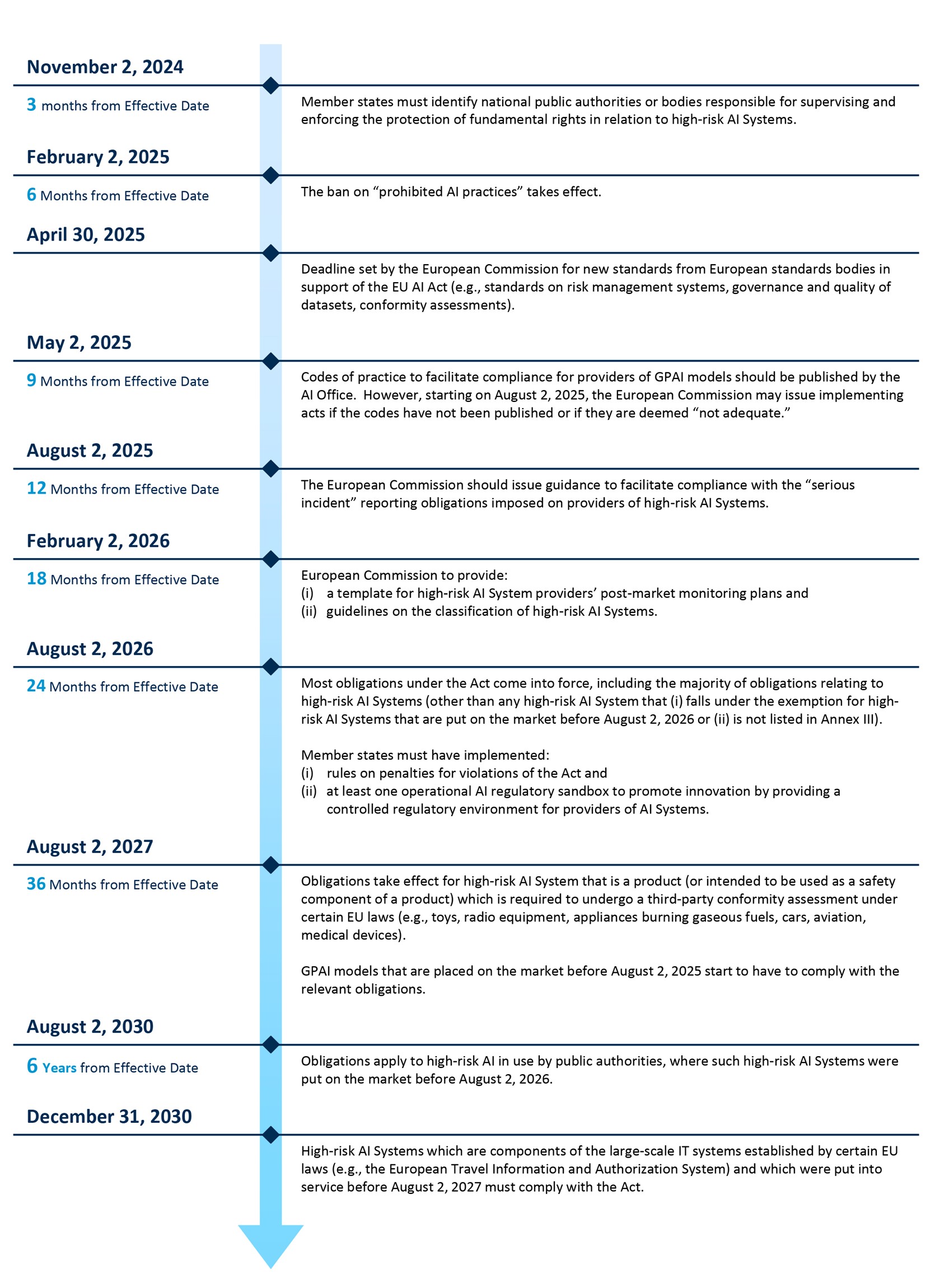

Under the Act, provisions will generally become operative on August 2, 2026. The below sets out the specific timeline for the effectiveness of key provisions:

* * *